Particle loading

Particles in EPOCH belong to particle species which can be controlled by the species block. In these examples, we show how to load macro-particles in various configurations. These macro-particle objects behave as single particles in the code, but represent many real particles for the current solver. The examples on this page set up simulations in epoch2d, but they may be modified for use in the 1d or 3d codes.

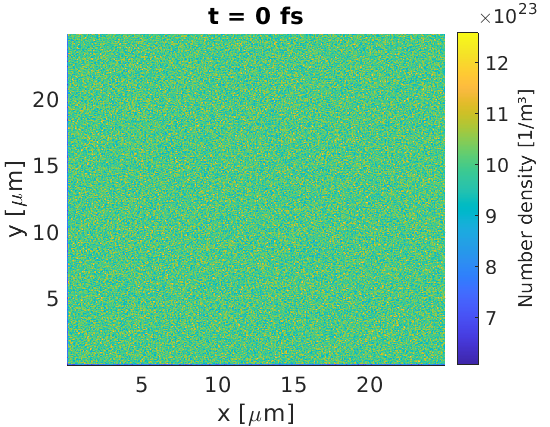

Uniform load

This basic input deck sets up a uniform density of electrons over the full simulation window. We create 10 macro-particles per cell, for a density of $10^{24}\text{ m}^{-3}$. The cell sizes are $dx = dy = 50\text{ nm}$ and $dz = 1 \text{ m}$, since cell sizes in omitted dimensions default to 1 metre. Hence, we expect $2.5\times 10^9$ real electrons per cell, so each macro-electron should represent around $2.5\times 10^8$ real electrons.

begin:control

nx = 500

ny = 500

t_end = 1.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = 25e-6

y_min = 0

y_max = 25e-6

stdout_frequency = 100

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = open

bc_x_max = open

bc_y_min = open

bc_y_max = open

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

npart = 50 * nx * ny

density = 1.0e24

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end

number_density = always

end:output

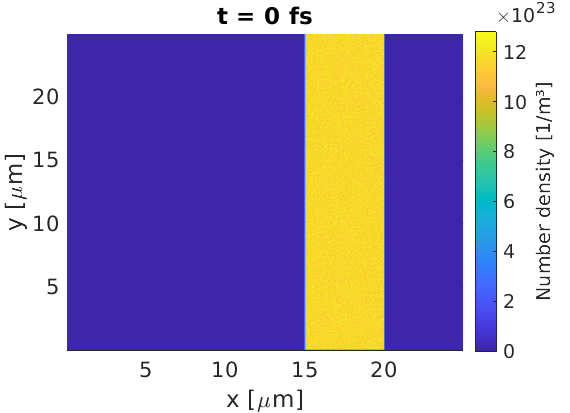

Basic target

The shape of the target can be controlled by using maths parser expressions in the density key. For example, a $5 \text{ }\mu\text{m}$ target slab can be defined according to

begin:control

nx = 500

ny = 500

t_end = 1.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = 25e-6

y_min = 0

y_max = 25e-6

stdout_frequency = 100

npart = 50 * (5.0e-6/(x_max-x_min)) * nx * ny

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = open

bc_x_max = open

bc_y_min = open

bc_y_max = open

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

frac = 0.8

density = if (x gt 15.0e-6, 1.0e24, 0)

density = if (x gt 20.0e-6, 0, density(Electron))

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:species

name = Carbon

mass = 22033.0

charge = 6.0

frac = 0.2

density = density(Electron) / 6

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end

number_density = always

end:output

This target contains both electrons, and fully ionised carbon ions. The number

of macro-particles loaded has been set to ensure there are 50 particles per

cell, accounting for the fact most cells are in vacuum. The if command in

EPOCH uses an if-else format, such that the line:

density = if (x gt 20.0e-6, 0, density(Electron))

means that for cells with $x>20\text{ }\mu\text{m}$, set the density to 0, and in all other cells, set the density to what it was already (no change).

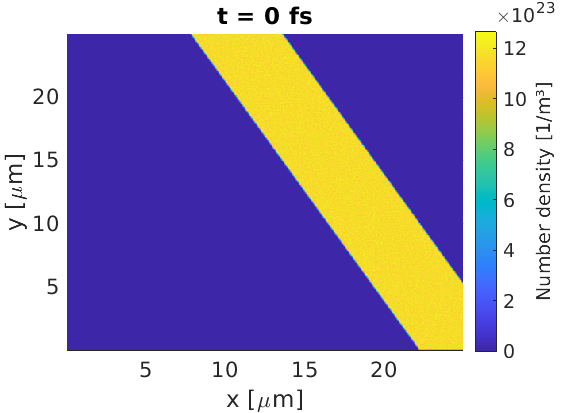

Rotated target

Let us take the basic target, and rotate it about the point $(15.0,12.5)\text{ }\mu\text{m}$. To do this, we can set new functions in a constant block to help.

We may use a rotation transformation

$x' = x\cos(\theta) + y\sin(\theta)$

$y' = -x\sin(\theta) + y\cos(\theta)$

to obtain $x$ and $y$ co-ordinates in a rotated co-ordinate system, which makes the writing of the input.deck more straightforward. An example input.deck is provided:

begin:constant

x0 = 15.0e-6

y0 = 12.5e-6

theta = 30.0 / 180.0 * pi

x_rot = (x-x0)*cos(theta) + (y-y0)*sin(theta)

y_rot = -(x-x0)*sin(theta) + (y-y0)*cos(theta)

end:constant

begin:control

nx = 500

ny = 500

t_end = 1.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = 25e-6

y_min = 0

y_max = 25e-6

stdout_frequency = 100

npart = 50 * (5.0e-6/(x_max-x_min)) * nx * ny / sin(theta)

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = open

bc_x_max = open

bc_y_min = open

bc_y_max = open

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

frac = 0.8

density = if (x_rot gt 0.0, 1.0e24, 0)

density = if (x_rot gt 5.0e-6, 0, density(Electron))

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:species

name = Carbon

mass = 22033.0

charge = 6.0

frac = 0.2

density = density(Electron) / 6

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end

number_density = always

end:output

By creating the x_rot, y_rot variables, we can define objects in a rotated

co-ordinate system. In this new system, the x0, y0 point is the origin, and

theta is the rotation amount in radians. The number of loaded macro-particles

has been increased by 1 / sin(theta) to account for the fact that more cells

contain particles than in the non-rotated case.

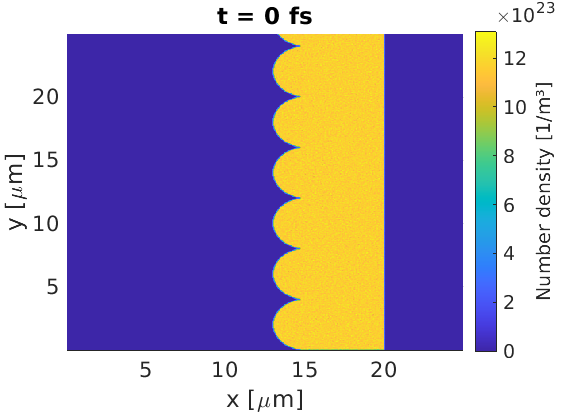

Periodic structure

We may use a certain trick in the

maths parser to generate

repeating structures. If we wished to add strucutre to the front surface of a

target, where the repeated unit had a size of $y_r$, then a variable y_f

y_f = (y / y_r) - floor(y / y_r)

would continuously repeat from 0 to 1 in each periodic window. This can be used to create a repeating strucutre.

For example, if the user wished to add a stack of half-spheres to the front of the target, they may use:

begin:constant

x_front = 15.0e-6

circle_radius = 2.0e-6

y_r = 2.0 * circle_radius

y_f = 2.0*((y / y_r) - floor(y / y_r))-1.0

end:constant

begin:control

nx = 500

ny = 500

t_end = 1.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = 25e-6

y_min = 0

y_max = 25e-6

stdout_frequency = 100

npart = 50 * (5.0e-6/(x_max-x_min)) * nx * ny

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = open

bc_x_max = open

bc_y_min = open

bc_y_max = open

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

frac = 0.8

density = if ((x-x_front)^2 + (y_f * circle_radius)^2 lt circle_radius^2,\

1.0e24, 0)

density = if (x gt x_front and x lt (x_front + 5.0e-6), \

1.0e24, density(Electron))

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:species

name = Carbon

mass = 22033.0

charge = 6.0

frac = 0.2

density = density(Electron) / 6

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end

number_density = always

end:output

Note: due to the target complexity, I have not tried to force 50 macro-particles per cell in this simulation.

Load density from file

Sometimes a density distribution can be too complicated to set up using the EPOCH maths parser. In this case, EPOCH can read a binary file where the density in each cell is specified.

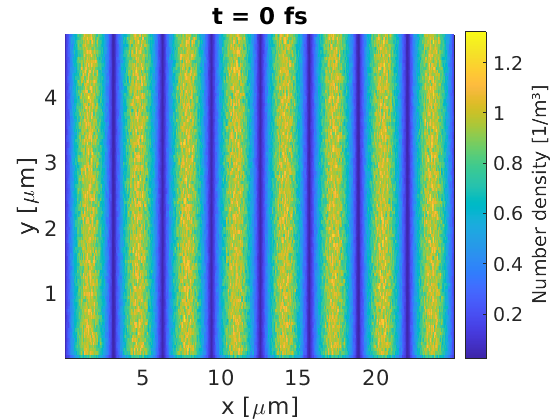

Binary files can be written by many coding languages. In this example, I used MATLAB to write a sinusoidal density profile to file, using the code provided here. Note the order of numbers being written - we perform a full line of $x$ values first, before moving onto the second line at the next $y$.

nx = 500;

ny = 100;

fileID = fopen('density.bin','w');

for iy = 1:ny

for ix = 1:nx

density = abs(sin(ix/20));

fwrite(fileID,density,'double');

end

end

fclose(fileID);

An input deck was created to read this binary, where I have specified the full path to the binary file position

begin:control

nx = 500

ny = 100

t_end = 1.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = 25e-6

y_min = 0

y_max = 5e-6

stdout_frequency = 100

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = open

bc_x_max = open

bc_y_min = open

bc_y_max = open

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

npart = 5 * nx * ny

density = '/home/examples/density.bin'

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end

number_density = always

end:output

This yielded the desired output for the density profile

Momentum distributions

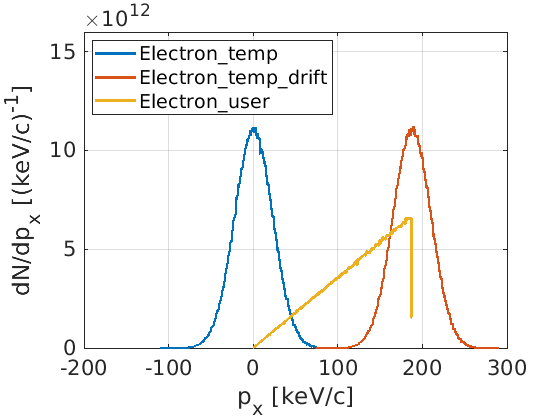

While the density key in EPOCH can be used to set up macro-particle positions,

the temperature and drift keys provide momentum distributions. The

temperature key samples a momentum from a relativistic Maxwell-Jüttner

distribution, and drift applies a Lorentz boost to these momenta.

The user may also specify their own momentum distribution, using dist_fn.

A functional form for the momentum distribution can be written in the

input deck, and

EPOCH can sample momenta from this distribution. As an example, say we wanted a

linearly-increasing distribution for the momentum x-component, from $p_x=0$ to

$p_x = p_{max}$

dist_fn = px / p_max

where the maximum value of dist_fn has been set to 1. When sampling, EPOCH

will generate $p_x$, $p_y$ and $p_z$ values within a user-chosen range, and

substitute these into the dist_fn expression yielding a number between 0 and

1. This number corresponds to the probability of keeping the sampled momenta,

or choosing a new set, which is sampled using a uniformly-distributed random

number.

As an example, the following input deck initialises 3 species. One using only temperature, one with the same temperature and drift, and the last using a user-defined function.

begin:control

nx = 500

ny = 500

t_end = 1.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = 25e-6

y_min = 0

y_max = 25e-6

stdout_frequency = 100

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = open

bc_x_max = open

bc_y_min = open

bc_y_max = open

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron_temp

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

npart = 5 * nx * ny

density = 1.0e24

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:species

name = Electron_temp_drift

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

npart = 5 * nx * ny

density = 1.0e24

temp_ev = 1000

drift_x = 1.0e-22

end:species

begin:species

name = Electron_user

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

npart = 5 * nx * ny

density = 1.0e24

dist_fn = px / 1.0e-22

dist_fn_px_range = (0, 1.0e-22)

end:species

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end

px = always

weight = always

end:output

Load particles from file

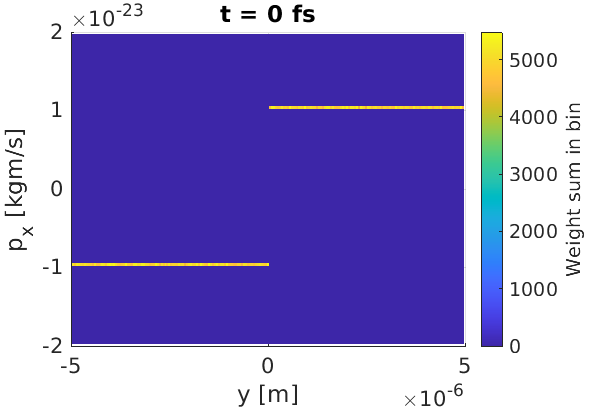

If the user requires spatial and momentum distributions too complicated for the previous methods, then they may perform the ultimate brute-force technique. Using the particles_from_file block the user is able to manually specify the position, momentum and weight of each macro-particle at the start of the simulation.

As an example, let us set up a simple simulation where particles above $y=0$ have momentum $p_x = 10^{-23}\text{ kgm/s}$, and where $p_x = -10^{-23}\text{ kgm/s}$ below $y=0$. We will also force a uniform density of macro-particles over the simulation window, and assign each macro-particle a weight of 10. The particle files to achieve this were written by the following MATLAB code

% Simulation parameters

part_count = 1.0e5;

x_min = 0;

x_max = 25.0e-6;

y_min = -5.0e-6;

y_max = 5.0e-6;

px0 = 1.0e-23;

% Set particle properties

x_vals = (x_max - x_min) * rand(1,part_count) + x_min;

y_vals = (y_max - y_min) * rand(1,part_count) + y_min;

w_vals = 10 * ones(1,part_count);

px_vals = px0 * ones(1,part_count);

px_vals(y_vals<0) = -px0;

% Write files

x_file = fopen('x.bin','w');

y_file = fopen('y.bin','w');

w_file = fopen('w.bin','w');

px_file = fopen('px.bin','w');

for i = 1:part_count

fwrite(x_file,x_vals(i),'double');

fwrite(y_file,y_vals(i),'double');

fwrite(w_file,w_vals(i),'double');

fwrite(px_file,px_vals(i),'double');

end

fclose(x_file);

fclose(y_file);

fclose(w_file);

fclose(px_file);

To load these macro-particles into the simulation, the following input.deck was used

begin:control

nx = 500

ny = 200

t_end = 1.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = 25e-6

y_min = -5e-6

y_max = 5e-6

stdout_frequency = 100

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = open

bc_x_max = open

bc_y_min = open

bc_y_max = open

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

end:species

begin:particles_from_file

species = Electron

x_data = "/home/examples/x.bin"

y_data = "/home/examples/y.bin"

w_data = "/home/examples/w.bin"

px_data = "/home/examples/px.bin"

end:particles_from_file

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end

distribution_functions = always

end:output

begin:dist_fn

name = y_px

ndims = 2

dumpmask = always

direction1 = dir_y

direction2 = dir_px

resolution2 = 100

range2 = (-2.0e-23, 2.0e-23)

include_species:Electron

end:dist_fn

Here, we have provided the full paths to the particle file locations. To visualise the distribution of macro-particles in position and momentum space, we output a distribution function to obtain the expected figure.

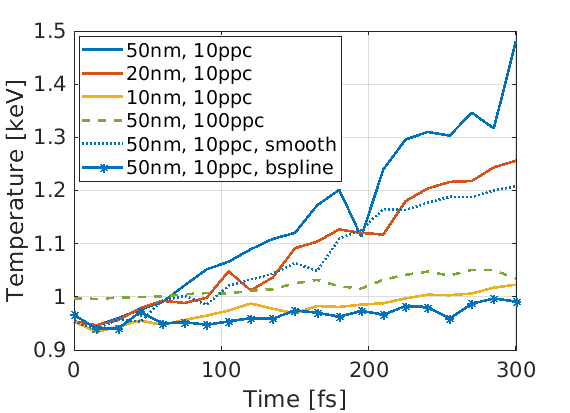

Self-heating

Low resolution PIC codes can result in self-heating, where macro-particles can gain energy non-physically. To measure its effect, we can simulate a small portion of the simulation and assign periodic boundary conditions. Self-heating can be reduced by using:

- Smaller cell sizes

- More marcro-particles per cell

- Current smoothing (see control block)

- Higher order macro-particle shapes (see pre-compiler flags)

Let us construct a test example, where we wish to find simulation parameters to prevent self-heating in a system with electron density $10^{28} \text{ m}^{-3}$ and temperature $1 \text{ keV}$. By omitting an ion species, EPOCH will assume the presence of a neutralising immobile proton population, at the same density as the initial electron population. An input deck has been provided for this test, and we can repeat the test for different cell-sizes, particles per cell, macro-particle shapes and current-smoothing status.

begin:constant

cell_size = 50.0e-9

parts_per_cell = 10

end:constant

begin:control

nx = 10

ny = 10

t_end = 300.0e-15

x_min = 0

x_max = nx * cell_size

y_min = 0

y_max = ny * cell_size

stdout_frequency = 100

smooth_currents = T

end:control

begin:boundaries

bc_x_min = periodic

bc_x_max = periodic

bc_y_min = periodic

bc_y_max = periodic

end:boundaries

begin:species

name = Electron

mass = 1.0

charge = -1.0

npart = parts_per_cell * nx * ny

density = 1.0e28

temp_ev = 1000

end:species

begin:output

dt_snapshot = t_end/20

temperature = always

end:output

As there is no source of energy in this simulation, any temperature increase must be non-physical. Here we see that as cell-size decreases, or particles per cell increases, the self-heating is reduced. Switching on current smoothing, or switching to a higher order macro-particle shape (B-spline) also reduces self-heating. All these features come at a cost of a greater runtime, so it is up to the user to decide how much self-heating mitigation is required.